By Saga Jakupcak

Trung Le Nguyen (lee-when) (he/ they) is an award-winning writer, illustrator, and cartoonist from Minneapolis, Minnesota. He is an Eisner nominee, GLAAD award recipient, two-time Harvey Award winner, as well as a Romics recipient.

Inspired by his upbringing, Nguyen’s novel The Magic Fish centers around a young boy and his mother, both immigrants from Vietnam who struggle to communicate with one another, facing both linguistic and cultural barriers.

Nguyen's work is bright and lively, drawn up for a young-ish audience, but the gravity of his storytelling elevates it to the status of being a universal classic for those of any age. In The Magic Fish, our main character, Tiến, is shown to connect to his mother through the sharing of fairy tales. This is at first glance a way for her to sharpen her English skills while spending time with her son, but as the story unfolds, the recounting of these stories is revealed to cloak something deeper, a venture into his mother’s mysterious past in Vietnam, as the fairy tales she recounts become more and more planted in reality, and in her strong love for her family.

After all, haven’t fairytales been commonly told to warn the younger generation about the perils and complications of the adult world?

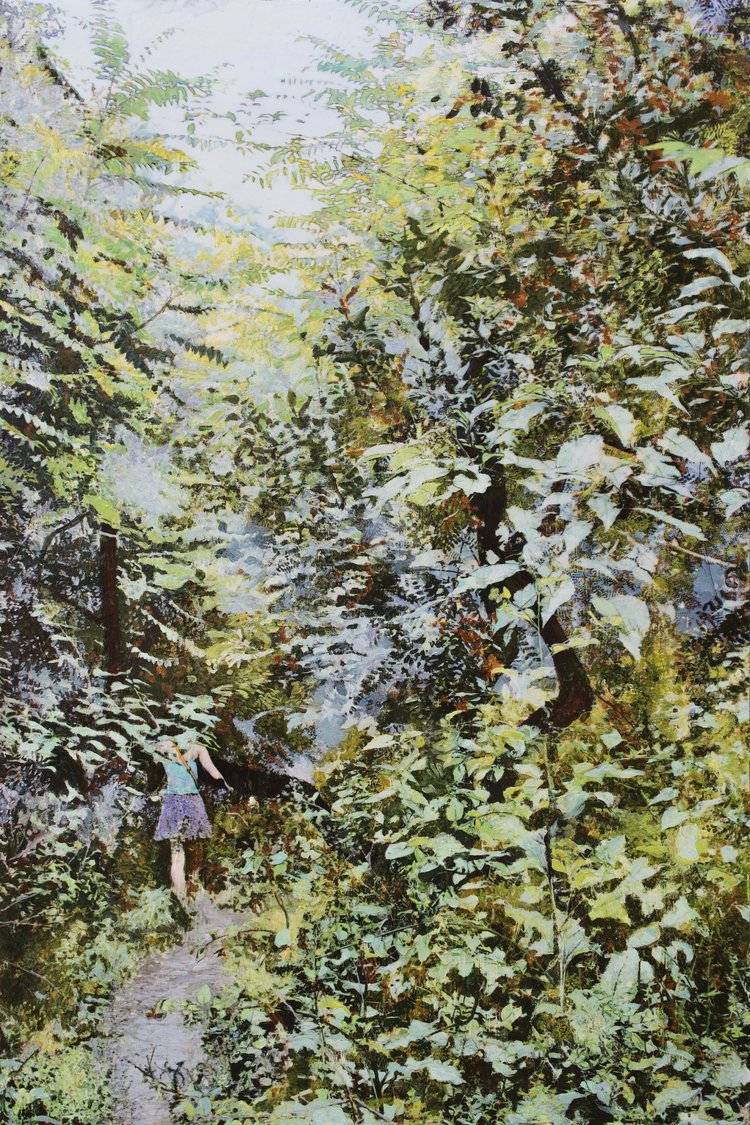

Trung’s art, detailed and sinuous, is eye-catching yet heart-wrenching. As an illustrator, he’s at his best rendering aspects of the natural world and the human world in collision. His characters are generally human, yet tend to have an otherworldly quality, such as mermaids. Indeed, his sketchbook and digital illustrations frequently include women or men with bird or fish motifs–such as mermaids and harpies, features which may bear great thematic significance given Nguyen' s propensity for inducing Tarot motifs in his work. (He has even created his own line of Tarot cards!)

Trung Le Nguyen continues to reside in Minneapolis, where he first got his start as a professional artist at the Light Grey Art Lab. He was a student at Hamline university, studying painting and art history before pivoting after his graduation to comics.

I myself have long been a fan of Trung Le Nguyen. When I first read The Magic Fish, in my early high school years, it resonated deeply with my experience of being a rapidly assimilating Nth generation Lebanese in America. However, my main takeaway from his novel at the time was the importance of the older generation listening to the younger generation, cultivating the connection that they have to their younger family, and communicating through sharing stories.

This October, I had the pleasure of sitting down with Trung Le Nguyen to discuss the process of creating his debut novel, The Magic Fish, as well as the importance of YA being read by adults.

Saga: At the center of The Magic Fish, we have both the immigrant experience and the cultural divide between the older and the younger generation. In your graphic novel, you explore how sharing of stories can help bridge that gap.

I was wondering, do you feel that there is a disconnect existing today between the older and younger generations?

Trung: Today, I actually don't know that that divide is quite as strong as it used to be. For example, one of my favorite things about living now is that there's so much access to media from all sorts of different eras that we weren't alive for. It’s becoming very easy to play catch up culturally–like, I've recently been watching a lot of the Carol Burnett show because I'd never seen it before, and to see how late night humor is being shaped in real time in the 70s, and then figuring out where those jokes land today and what works and what doesn’t…I find to be incredibly cool that we can do that now and, it seems, every time I talk to younger people, they're watching the shows that I grew up with. They can talk to me about Gilmore Girls. People are still watching 30 Rock. People are watching Columbo. Like, the kids are watching Columbo. It's kind of amazing. There are so many opportunities for the cultural divide to be bridged with a little bit more intention. I think a lot of it comes down to wherever there is a cultural divide there is also a hesitation to engage with a lot of this different media that we have floating around.

But I feel like that gap is getting smaller. The disconnect is not as great as it was when I was a kid.

Saga: It's interesting that you mentioned going back and looking at older media because I've noticed a lot of the same thing here on the UMN campus, especially when we talk about cultural experiences. Students are very interested in the history of their ancestors. What I don't tend to see is a lot of the opposite happening: the older generation gravitating towards younger stories, about younger people. Do you think it's important for adults to turn to younger literature as a means of seeing and understanding what “the kids” are going through these days?

Trung: Yeah, absolutely. That observation is so astute.

I think that younger folks in general are interested in the past. Today, younger folks will look at things that existed long before them, and they'll get a lot out of it. They also know how to have conversations about things within the context of their time. I’ve found that a really mature kind of digestion of literature is happening with younger viewers and younger readers, but with older folks there seems to be a slowness to look at what's going on today. There's this sort of double edged sword of the things that have shaped them culturally are the things that are important to younger folks today, so they're likely getting a sense that the things that they know are all that they need to know, and so there seems to be a disinterest in engaging with media made for younger people today. So, yes, there is a bit of an imbalance there. I feel like older people would be much enriched by it. I understand that a lot of the themes included in younger literature and YA literature in particular, center around coming of age stuff, which includes a lot of really big feelings. And I understand that, as you get older, you tend to have less time for those feelings because you've had them before and they just don’t occupy a huge emotional space within the history of your feelings. However, for the younger people experiencing them for the first time, they are important and older folks should be able to remind themselves that, actually, within the scope of their lives, these things are very, very important. We have to relearn how to empathize all the time with people who are at different points in their life.

Saga: Would it be fair to say that the main character is very much tied to who you were and what you were experiencing at that age?

Trung: Yeah, yes, there are definitely some things that happened to the character that are more or less pulled out of my life. I mean, I'm sure there are some differences, but I think that the main character is very heavily drawn from my experiences when I was young.

Saga: Is it hard to, do you find, or is it getting harder to write about that period of your life?

Trung: I think a part of the project of The Magic Fish was that I didn't want to tell a story that was straight up autobiographical. I would be comfortable describing it as semi-autobiographical, because a lot of the story is a total work of fiction that only draws inspiration from my life. But I did find that when I was making the story, the main character, Tiến’s story is told kind of at a remove. I'm actually much more emotionally close to the character of his mother. We’re similar in age, and I feel that her sense of interiority is something that I was just a little bit closer to. When it comes to writing the middle school aged characters, I have a lot of faith in my readers to be able to bring out the interiority of the characters as long as the characters are doing things that are meaningful to them.

It's sort of like with fairy tales, where the characters are archetypes and possess an inherent flatness to them. The characters in fairy tales don't really have an internal psychology that's ever explored because they don't need that in oral storytelling. Oral storytelling is more about revelatory experiences between the two of you, the people who are present in the space of the telling. So, when it comes to writing younger characters, I feel like I don't need to remember everything. All I need is to be clear about what happens. And I think readers will be able to bring their own experiences and they will be able to work with the text in order to bridge whatever gaps there are that I'm leaving within the literature.

Saga: Certainly, and that reminds me of something that you included at the end of your novel. It was your acknowledgements page. You wanted to tell your readers that this is a very cookie-cutter fairy tale story, and you wanted to caution them against conflating the entirety of the immigrant experience with just one sort of story. Would you be willing to further explain your acknowledgements page and what you specifically didn't want your readers to take away from this story?

Trung: Sure. When I was writing the back matter, I was turning over the idea that oftentimes narratives about immigrants are told through the lens of the news, and, so, that narrative becomes very rote, it becomes very formulaic. We (society) look at the lives of immigrants and all oppressed people in very, very broad strokes because we can’t account for the hundreds of thousands of lives that go through these same motions. That is because our lives are ruled by the institutions through which we navigate.

We are going to have a lot of similar experiences. For example, we have our sponsorship experience, our green card experience, all of those things. A lot of people have gone through those experiences. But, when we look at those stories, from just that very broad point of view, I get the sense that folks don't want to become emotionally involved. People can start to regard immigration as a curiosity instead of this thing that people go through that can be really fraught and really difficult and very emotional and exhausting. And it takes years and years of your life. So I think with The Magic Fish in particular, I really wanted to remove myself from the responsibility of being an expert on immigration writ large, and instead focus on the emotional beats of the characters and making sure that I’m accessing readers' empathy as opposed to just their curiosity. It became an exercise in looking at things in a very small way to become obsessed with the minutiae of the characters.

Saga: I'd love to move more into the themes of your work and the ways in which you portray the young LGBTQ experience, because I noticed some things when I was reading. Within the fairy tales, you can see queerness present, though it’s kept a metaphor. For example, Alera is initially incorrectly seen as a boy as opposed to a girl by Prince Maxwell. There are all these metaphors for the queer experience, but none of them are outright. What do you think is the value of containing that metaphor within your work, but not making it explicit?

Trung: This is a situation wherein I'm having my cake and eating it too, because some of the stories are very metaphorical, and then, towards the end, one of them becomes very not metaphorical, it becomes explicit, and the subtext becomes the text towards the end of the book. I think that mode of storytelling is something that a lot of queer people are really used to. Most of us grew up with media where you are required to read between the lines in order to understand that we're there. That isn't something that we have to do so much nowadays. And so, I kind of wanted to include that experience within that story where, whenever there is hesitation, queerness becomes the subtext, and when there's acceptance, queerness becomes the text. Though I felt it was important, it wasn't something that I had planned on doing on purpose. It was an instance where I just couldn't help but to include something that represented a facet of my lived experience into the book.

Saga: This is just an observation, but it seems that keeping things in the subtext also, in a lot of ways, gains authors a wider readership. I know that certain types of readers can become disinterested if they are reading something they cannot relate to. So it helps move the story along and integrate people.

Trung: Right, yeah. I wrote that as a kind of disclaimer. I'm not trying to give training wheels of empathy to straight people, you know?

I spent years of my life watching, for example, Nora Ephron movies, and rooting for Meg Ryan, and, to be honest, my life has no parallels to this. I have no trouble doing that. I believe in our straight readers and their ability to empathize. Though, to be sure, I do like playing with subtext and with texts that way, just because I feel like that it's just a part of queer history: that we've had to contend with subtext that way for such a long time.

But, no, I'm unafraid of making straight people have a little compassion.

Saga: One thing I’ve noticed is that a lot of your novel is very dependent on the reader–to have empathy, to use their discretion, to use their brain to understand that this isn't the entirety of the experience of being young and gay or being an immigrant. Were you ever nervous at all while writing and illustrating this book, because it is kind of a vulnerable, emotional, and somewhat heavy book, albeit one in comic format?

Trung: When I started working on The Magic Fish, the framing device story actually was not the center of it at all. That was something that came afterwards, because I had originally pitched my story as being largely just an excuse to tell my favorite fairy tale story in comic book format, and then my agent (and eventually my editors) encouraged me to be a little bit more personal. So, the framing device story kind of came after the fact, after examining why these specific stories/ fairy tales were important to me.

Connecting those threads between the fairy tales. and the lived experience of immigrants and of queer people was something that arose over the course of the telling of the story. I did not intend for The Magic Fish to be as heavy as it is, however, it kind of wound up being the shape of the story. I sort of just went with it because I thought that it worked really well. And so, I don't know that the heaviness of it in and of itself was a challenge at the beginning, but it did become a challenge to me over the course of the telling of the story due to the fact that it wasn't my initial intention to be quite so personal and to get quite so heavy.

I think the biggest challenge that I found myself struggling with in the story was–and I think a lot of people who exist within the diaspora kind of feel this way–where you grew up in this place where you are other, and that's fine because you're acclimated, you're assimilated…But, when you tell stories about yourself, there's this expectation that you need to be an expert in the place where you're from, even if you have very little lived experience in those spaces. I felt like a fraud. I thought, “I think people expect me to know more about Vietnam than I do.”I had this kind of weird moment where I was like, “oh no, am I culturally appropriating my own family's culture?” Which is so silly, right? It's such a strange double bind. Eventually, I realized that the notion of authenticity in storytelling is something of a double standard because we, as a society, don't tend to expect people who are existing and writing from the hegemony to explain themselves all the time. If you're writing from a marginalized background, there's this sort of temptation–and a lot of times it's encouraged, too–to explain yourself. “Why are you here? How did you get to be here?” I had to let go of that preoccupation.

I realized that I don't have some sort of special responsibility to edify the public about my experiences. I just want people to empathize with these characters that I'm breathing life into. That was the start of me being able to understand the fact that my experiences are genuine because they're mine, and I don't need to serve as an ambassador for this place where I've spent so little of my life. If I really needed to know more about it, I have living resources that I can talk to. I'm in the fortunate position of being able to talk to my grandmother or my parents about these things. Ultimately, this is about understanding that the in-betweenness of being a part of the diaspora is in-and-of-itself a space, and that space is valid. And I love existing in this space because this is where I find my feet every day. So it's like figuring out how to make a home in places that people consider to be liminal. I tend to think there's this obsession with liminality whenever people discuss immigration, but I like that space because I am here exactly in that space. In fact, telling stories from that space is something that I really indulged in.

Speaking, you kind of feel like a little dilettante. You're like, “Oh, I'm not the expert here.” It's like, “Who am I?” You start thinking these people know better than you do. And then it's like, “What do they know versus what I know?”

Saga: But you mentioned you dedicated this work to your parents. And The Magic Fish heavily features Helen (Tiến’s mother). Were there any kind of concerns or even just things that you wanted them (your parents) to notice within your work, for example, an acknowledgement of them?

Trung: Oh, yeah, no, not at all. Which sounds nuts. I think I wrote the book with the notion that my parents did everything right in terms of the way that they treated my queerness. So, it was more like “I don't think that you need to get anything out of this. I think you just need to understand that you inspired me to make this thing because you're special to me.” I didn't want them to feel like they needed to get anything out of it. I just thought they'd get a kick out of it. It was just sort of my way of saying, “you’re very special to me.”

Saga: I think a lot of our writers should be able to relate to that. Another thing that I’d love to speak to you about is your layering of themes and symbolisms. As an author, you are very adept at driving narrative and layering symbolism. For one, you include colors that indicate different settings, for example: yellow represents a flashback. Red is when we're focusing on our main character and his mother. Blue occurs when our story enters the realm of the fairytale. However, there's one specific part where I felt I kind of lost the plot. It’s on pages 105/106 when Alera is confronting the old man of the sea, and her aunt velvet intervenes. It's such a big moment and I feel like there's something deeper trying to come out, some sort of greater form of inspiration that I'm missing.Would you be able to speak more about that?

Trung: I'm not one of those authors who needs readers to have a “correct” interpretation of my work because I want to honor whatever they bring to the table. But we talked about this, like, metaphorically– this scene is the stand in for my own experience of having the realization of, “Oh, I don't need to belong wherever it is that other people tell me I belong. I belong exactly where I belong. Here.” And so, that moment where the old man of the sea insists that Alera needs to return to the sea and that she belongs to him originated from my own struggle of, like, “Do I belong to the culture that my parents come from?” Because I feel very much entrenched in the culture where I grew up, which is right here. So, what is this expectation that's pulling me back? And then kind of understanding that I'm right here, where I'm supposed to be and that where I grew up and where I find myself now is completely valid, both from a storytelling perspective, but also from a cultural and personal perspective. And so, in a way, that scene was my catharsis of, like, “no, I belong exactly where I am.”

Saga: So her aunt intervening is like a big realization, the sort of release of pressure of this thing that's been weighing on her (you). I think I understand now.

When we talk about themes, the conversation can get quite serious. Another thing that I wanted to query you about, that, I feel, if I didn’t, would be a deprivation to all of our Arts and English students who might be tuning in: Where did you discover your art style? It’s gorgeous, and the emphasis that you place on your female character’s hair is so unique in the way it reads on the page.

Trung: Sure! My background isn't actually in comics, it's in painting and in art history, history more so than painting, despite the fact that I technically majored in painting and minored in art history. I had the total joy of working with a professor at Hamline by the name of Professor Aida Aouda, and she's fantastic. Her greatest muse was always Dante, and I remember she loved looking at all the iconography around Dante. She was someone who had very specific interests and her influence really encouraged me to build my own kinds of interests around art history. We took survey courses, and she allowed me to get more specific outside of the curriculum and that was when I realized that I had interest in the relationship between the available technology and the ways in which images are printed. I became very fascinated with turn of the century children's book illustration from the golden age of illustration before the early 1900s.

I’d say that a lot of my art style tends to resemble all the pictures that I enjoy looking at from that era. I like looking at a lot of ephemera and children's books from that time. And a lot of the illustrators sort of came out of the arts and crafts movement out of Art Nouveau, and through this a lot of those aesthetics

also made their way into my work. There’s also a healthy dose of Sunday strip comics and manga in there, too. But my real “visual love” is turn of the century children's books. And so, as it would happen, a lot of them just tend to bear that resemblance: they look like Edmund Dulac works, and they look like Harry Clark, and Rose O'Neill. All of those artists serve as places from where I draw a lot of influence.

All of this led me to enjoy having aesthetic spaces that are very, very busy and very ornamental, flushed up against spaces that are very sparse.

Saga: Reading the book I certainly got the fairytale book aspect of it. That's why I bought a copy for my younger sister because it's just so wonderfully calming to look at. But it also looks so labor intensive. When you were studying at Hamline, how on Earth did you find the time to work on comics, even as a hobby?

Trung: Well, I mean, I wasn't working on comics, really. I was largely just drawing little spot illustrations for myself, because I was majoring in oil painting, though that’s something I don’t do anymore. Majoring in Oil Painting was good for me, but it's not a skill I have necessarily taken on into my professional life in the way that I thought that I would. But it was relaxing. The way that I draw the hair is sort of meditative to me, and I was a very stressed-out student, so it was a really nice time for me to slow down and breathe and be very intentional while having something pretty to look at.

What I've discovered is that, and this is a little bit surprising, the very ornamental, very busy, portions of my images, for example the hair, are actually the easiest part. All I have to do is come up with the composition for it, and if I make a mistake with one of those lines, I can just add another line right next to it, and then because they're right next to each other, it builds into a broader gesture. I find it to be very easy and very forgiving. The parts of the job that are hard are the ones where I have to convey a shape with one single line because of all of the pressures on that line. So, while it may appear to be the most difficult aspect, I find that drawing the hair is much more forgiving than all the other aspects of composition.

Saga: Did you happen to take any digital art courses while you were at Hamline University or were you completely focused on studio art and painting?

Trung: Yeah, no, it was all traditional media. I learned how to work digitally for The Magic Fish because there's a portion in the book that I drew traditionally, but because I wanted to meet my deadline, I had to learn how to draw in Photoshop with a tablet. And that feeling of drawing on glass was a terrible experience! I really hated how slick it was. I prefer the tension of materials rubbing against each other. I've since gotten a lot better at it, but I had to learn how to draw digitally more or less on the job. It was very challenging.

Saga: Well, it's encouraging to hear that because sometimes as a young art student, you can see artists who are further along in their career and think to yourself: there is no way on earth that they were anywhere near my level at my age… but it seems like everybody goes through that phase of uncertainty.

Trung: Oh, for sure. I'm a huge proponent of, especially in the case of younger artists, I really want them to make things that don't look perfect. We should all be free to make things that are really kind of crappy looking because, one, they're very charming—but you also learn a lot from just messing around and experimenting. I think my work looks very exacting, but there's still so much uncertainty. For example, I like my sketches, so my pencil phase is largely unhelpful to me when it comes to the actual inking portion of it. It’s a very imprecise thing. I don’t enjoy feeling bound by things. I have this mentality of: let the lines fall where they may and then I just adjust as I'm working. I enjoy having space to do things that are surprising.

Saga: Speaking of where you're at right now, obviously you're still located within the Twin Cities area. I’m curious to know: What has really kept you here? Most artists I see tend to gravitate towards the coasts–East or West.

Trung: The easiest answer is that I love it here. I can't imagine living anywhere else. Growing up, my parents–when they were sponsored to come over to the United States–their sponsor family was from Minnesota. And so we moved to the Twin Cities.

We lived in South Minneapolis for a couple of years. They lived in Stevens Square over by MCAD when I was really, really little. And then we began to gradually move out to the suburbs. I had never gotten to spend a lot of time in the cities, but I'd always wanted to. Then, I went to school in St. Paul, and now I live in Minneapolis. And so, I kind of feel like I'm still just starting to get to know the Twin Cities. And I really, really love it here.

I think the reason why so many artists go to the coast is the stereotype that says you go to the west coast if you want to work in animation, and you go to the east coast if you want to work in publishing, because that's where all the big publishing houses are.

There are a lot of practical considerations if you're an artist and you want to be a part of that bigger community and work on larger projects. I understand a sense of enchantment with the coast, but I like being here. And I don't love to go to conventions. But being in the Midwest means that you're at maximum a two-to-three-hour flight away from either coast. So, it's very easy to get there. It's a nice central location. Also, nobody bothers you.

Saga:

Except me.

SAGA JAKUPCAK is an English Major at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. She is a professional writer, aspiring author, and all around creative-type.

Want to read more great interviews? Great River Review now offers individual issues for sale. You can purchase a copy of GRR 71, GRR 70, or a number of other back issues, here.